| The LookOut columns | What I Say |

|

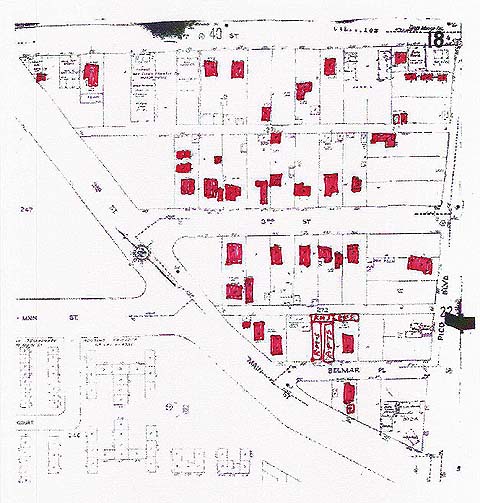

By Frank Gruber Readers may recall that a few months ago I wrote some columns referring to information I had come across in the course of research on events that took place in Santa Monica in the 1950's. I wasn't trying to be mysterious, but I never mentioned what the events were that so interested me that I was reading 50-year old City Council minutes. For various reasons, I am ready to come clean. One reason is that it gives me the opportunity to plug a lecture that the Santa Monica Conservancy is sponsoring on Sunday, Feb. 26. Alison Jefferson, the USC graduate student whose research lead to the landmarking of Phillips Chapel, the historically African-American Church at Fourth and Bay, will be speaking about forgotten history in Santa Monica. (The lecture will take place at the chapel at 2 p.m.; more details below.) Another reason is that the events I have been researching turn out to be relevant to the city's ongoing conversation about "neighborhood character" and how to preserve it. These were events that Ms. Jefferson could identify as "forgotten" but which, with her help and that of the Santa Monica Historical Society Museum, I hope will be in the future remembered. What I have been researching is a small African-American neighborhood known as the Belmar Triangle that the City emptied out and destroyed to provide the land for the Civic Auditorium. The neighborhood took its name from a little street called Belmar Place that ran one very short block north of Pico from a point just east of Main Street. In the map below, you can see that it creates a little triangle at the base of "Y" formed by Pico and Main.

This map is from 1950 and is what's called a "Sanborn Map." The Sanborn company published maps for the insurance industry that showed all the existing structures and how they were constructed. In the map, you can see that Third Street also continued north from Pico until it turned east on a diagonal to connect with Fourth Street. Belmar Place, Third Street and the alleys behind them, created a tight little urban grid. I have colored in red all the structures the Sanborn map identified as houses and outlined the apartments. The other buildings are businesses. I became aware of the Belmar neighborhood several years ago when I attended one of the many workshops on the Civic Center plan. An elderly African-American woman there was quite interested in what was planned. She said it was because she used to live there, and she said that the area used to be the center of black business in Santa Monica. What she said rang certain bells for me; it explained why an African-American church might be at Fourth and Bay, and why the now closed Allen Janitorial Supply, a black-owned business, might be (then) at Fourth and Pico. (I learned later that the first black doctor and other black professionals had their offices in a building that still exists at 424 Pico.) I also remember once when I was on the Planning Commission that for some reason we saw an old plot map of the area, with the old streets, peeking out from underneath what is now the Civic Auditorium parking lot. I felt an immediate yearning to restore an urban ecology -- the same feeling a swamp biologist might have looking at a degraded wetland. The Belmar Triangle neighborhood was a victim of "convulsive urbanism." This is a term UCLA professor (and Ocean Park resident) Dana Cuff coined to describe the rapid change that occurs in a city when big plans take precedence over existing land uses. Prof. Cuff discovered in her research about Los Angeles that contrary to the "organic" model of gradual urban evolution that historians have generally ascribed to the city, it often happens instead that great, "convulsive" events have a bigger impact. (You can read all about convulsive urbanism in Prof. Cuff's book, The Provisional City: Los Angeles Stories of Architecture and Urbanism.) In the case of Belmar, the good people of Santa Monica worried after World War II that they needed to replace, in the words of an Evening Outlook editorial, their "shabby 30-year old resort facilities." This belief eventually lead to the obliteration of the dense collection of hotels, amusements and housing along the beach in Ocean Park. At the time he wrote those words, however, the Evening Outlook editorialist was thundering about the need for a civic auditorium, without which Santa Monica would be sure to lose out to "Westwood or some other wide awake community close to the Bay district." Santa Monica had been assembling an imposing civic center since the 30's, when the City built City Hall where there had been a railroad depot. Then came the courthouse on the site of a building products yard. The Belmar Triangle and the African-Americans who lived there were in the path of destiny. What's more, they lived in what the City called a slum, and slums had to be cleared. Here's a picture of city officials proudly burning a Belmar house once all the condemnation proceedings were complete.

When the City sold the property across from City Hall to RAND, land that was then the site of temporary housing for World War II veterans, the City Manager was able to report that the sale not only finally resolved the problem of the veterans housing (meaning it had to go), but also that the $250,000 received from RAND gave the City enough money to proceed with "condemnation and clearance" of the Belmar Triangle for the civic center. The City commenced eminent domain proceedings to do just that, but the RAND sale did not provide enough money to build the civic auditorium. That required a bond issue, which required a 2/3 vote of the people. The bond passed, 21,377 yes votes to 4,280 no: a 5:1 margin. (Coincidentally this occurred at the same election that Santa Monica voters defeated a proposal to drill for oil in the bay; at least one can credit Santa Monicans with having enough sense to save the bay even as they destroyed a neighborhood.) Was Belmar a slum? Here's a picture of a house at 430 Pico.

One day I walked past this house with former mayor Nat Trives, who remembers the Belmar Triangle. He did a double take -- he told me that this house was just like those he remembered from Belmar. Fifty years later, it's still standing, well painted, with flowers, worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Meanwhile, the Civic had some glitzy moments with the Academy Awards and whatnot, but within a decade or so of its construction, the Civic Auditorium was being called a white elephant. Consider this: 50 years after selling land to RAND for $250,000, the City bought most of it back for $53 million. That's some appreciation. Too bad the black families the City forced out of Belmar didn't get to realize the same profits. What would have happened if the City had left Belmar alone and built the auditorium, say, downtown? Counter-factual history is always dangerous, but I suspect you can get a good idea by walking around the neighborhood on the other side of Pico -- Ocean Park, where the Phillips Chapel still stands. If you look at the 1950 Sanborn maps south of Pico, you will see a development pattern not much different from that of Belmar at the same time -- mostly small, unassuming houses on otherwise empty lots. Many of these houses still exist in Ocean Park, and they look a lot like the houses the City burned in Belmar. In fact many of the Ocean Park houses were probably "slum housing" by the City's standards in the 50's, judging by how many of them were ultimately abandoned. The difference is what 50 years' of lot-by-lot, building-by-building, addition-by-addition, dollar-by-dollar, non-convulsive change has wrought. Ocean Park, like many neighborhoods in Santa Monica, is now a wonderful place to live, with "character" that everyone wants to preserve. It has a rare mix of single-family houses and apartments, of varying architectures. Even after 25 years of escalating home prices, because of its diverse housing stock, it retains a population that is socially diverse. Fortunately, big plans didn't destroy Ocean Park in the 50's, but just as fortunately Ocean Park wasn't "preserved" either. The problem with planning for change is that by its nature, it conjures up abrupt change in the three physical dimensions. The problem with not planning for change is that you can't stop time. We should find the future of planning in the fourth dimension, time -- a lot of it. I have no fantasies about restoring the urban ecology of the Belmar Triangle. But the City plans to build a park there as part of the Civic Center plan. Maybe we could call it Belmar Park. Details on Alison Jefferson's talk: Revelations of

Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church: Forgotten History

in the City of Santa Monica; Sunday, Feb. 26, 2006, 2:00 p.m., Phillips

Chapel, 2001 Fourth Street, Santa Monica. Tickets (sold at the door):

$15; $10 for Santa Monica Conservancy members. More info: (310) 485-0399,

or www.smconservancy.org. | |||||

| If readers want to write the editor about this column, send your emails to The Lookout at mail@surfsantamonica.com . If readers want to write Frank Gruber, email frank@frankjgruber.net The views expressed in this column are those of Frank Gruber and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of The Lookout. |

Copyright 1999-2008 surfsantamonica.com. All Rights Reserved. |